What Parents Want: How Policies Can Spur School-to-Family Connections and Build Trust

Brief

Natalya Brill/New America

June 18, 2025

Helping parents and caregivers feel connected to their children’s school may sound as easy as hosting a back-to-school night. But on-the-ground stories from educators and parents show a desire for more. Caregivers all over the country are demanding better communication and more respect for their concerns, and whether that’s tied to the parents’ rights movement or not, there is mounting research about the benefits of improving school-to-family dynamics.

Fortunately, both schools and families want change. Parents want to be part of the conversation with teachers and school staff in helping their kids succeed, and principals and teachers want to forge better relationships with parents.[1] But it will take new strategies to overcome the myriad time and resource constraints, cultural differences, misunderstandings about schools and families, and language barriers that get in the way.

Over the past school year, 2024–2025, a group of education leaders in southwestern Pennsylvania, working with a program called Parents as Allies and a team of innovators from outside their districts selected by New America’s Learning Sciences Exchange (LSX) program, resolved to tackle some of these issues. They began with the premise that instead of pushing messages to parents and trying to get them to listen, school leaders should flip the script, listening to parents first. They also committed to redesigning systems that were not working well.

“Don’t assume you know what parents need,” said Tara Garcia Mathewson, one of the fellows involved in the project, reflecting on the team’s starting point for developing useful tools. “Talk to parents and identify what they need and work from there.”

Tabitha Marino, an assistant superintendent of New Castle School District and another fellow on the project, said talking to parents was one of Parents as Allies’ key messages. “Once schools start inviting parents in, working with parents and communicating with parents, that’s when everything starts moving in the right direction, that’s what fosters that student success,” Marino said.

By the time these innovators had finished their projects, they had designed four new resources and approaches for engaging with families in their districts, working with and eliciting feedback from parents along the way. Their simple tools and techniques, which can be borrowed and adapted in schools and districts around the country, are examples of low-cost solutions that can have a big impact in building trust and creating conditions for lasting relationships between parents, caregivers, school leaders, and teachers. These relationships build social capital, strengthening communities in the long run.

Applying the Research on Family Engagement and Student Success

This year-long experiment was started by LSX, a fellowship model that invites mid-career experts from different fields to collaborate and build a shared language for solving problems.[2] LSX focuses on communicating and applying the science of learning. In this particular challenge, it drew from scientific studies that emphasize the role of adults—whether parents or educators—in motivating children and selecting activities and resources that help them to do well in school.

Over the past 35 years, the research on the role of the adults in children’s lives has dovetailed with research on how parents interact with their children’s teachers and schools, and how much those interactions affect children’s academic success.[3] Scores of studies have investigated multiple dimensions of parent-teacher relationships and family-school partnerships.[4] Among the many findings, experts stress that there is a crucial distinction between family involvement, often characterized by parents attending school events or volunteering, and family engagement, in which parents and caregivers work with teachers in shaping their children’s learning experiences, setting mutual goals for their children, and making decisions alongside educators.[5]

Building on this distinction, scholars have emphasized the home, school, and community as major settings to support children’s well-being and success in school. Fifteen years ago, the National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement (NAFSCE), a membership organization for educators, parent liaisons, community engagement specialists, and school leaders, devised a comprehensive definition of family engagement. In 2024, it published a strategic framework, which, among other commitments, aims to “share power with families as full and equal partners in their children’s learning and in school improvement.”[6]

The work by NAFSCE and other education organizations also builds on decades of studies showing that children’s success as learners begins at home, early in their lives, where parents and caregivers act as children’s first teachers, laying the foundation for lifelong learning. When parents and children read together, tell stories, and play educational games, they build early literacy and math skills.[7] To supplement and encourage these home-based activities, schools have begun to provide more opportunities for parents to connect with educators through family nights that highlight special cultural connections and showcase students’ projects, as well as through family workshops and parent-teacher councils. These efforts foster student success and empower parents to advocate for their children.[8]

Community-based partnerships also play a crucial role in kids’ success by connecting families to local resources and networks of support. Partnerships between schools, libraries, afterschool programs, community centers, universities, and cultural organizations foster meaningful learning opportunities for children and families, and underscore the importance of neighborhood and community contexts.[9] These cross-sector collaborations, such as Abriendo Puertas/Opening Doors, have been shown to improve parents’ understanding of literacy development beginning at home, and they emphasize the need for culturally relevant materials to support student learning. Collaborations between libraries and literacy and STEM coalitions contribute to children’s academic and emotional well-being. Remake Learning Days, a multi-week-long regional festival of learning—which got its start in Pittsburgh—is a vibrant example, featuring in-school and out-of-school hands-on learning activities for families throughout different neighborhoods. And PBS stations across the country have collaborated with libraries, housing authorities, and community centers to expand services that promote good educational outcomes and empower families as advocates for their children’s learning.[10]

“This co-design approach, as it is becoming known in education circles, makes families into collaborators, rather than passive recipients of information or merely event attendees.”

This burgeoning community context means that schools today have many partners to lean on and parents’ experiences to build upon. This has sparked a new approach to family engagement: to design solutions with parents and caregivers, rather than presuming to design programs for them. This co-design approach, as it is becoming known in education circles, makes families into collaborators, rather than passive recipients of information or merely event attendees.[11] It fosters trust, increases relevance, and promotes stronger connections between home and school. Co-design reframes family engagement not as a one-size-fits-all outreach effort, but as a transformative, community-centered process that advances educational equity.

Laying the Foundation for Conversation, Dialogue, and Empathy

New America announced the latest cohort of LSX fellows on September 18, 2024 and the design-thinking sessions started the next day, represented by this picture of the fellows’ early brainstorming.

Source: Photos by Elise Franchino used with permission

This year’s project started with a team of innovators made up of seven experts chosen in a competitive selection process to become the fourth cohort of the LSX fellows program. These seven people included three school leaders in the Pittsburgh area, one researcher, one journalist, one social entrepreneur, and one children’s book author, who is a former educator who has consulted with school districts on improving relationships with families.

LSX tapped these fellows to work with Parents as Allies, a program started in 2021 by Kidsburgh, a family media project in Pittsburgh. By 2024–2025, Parents as Allies had established parent-educator teams in 31 school districts across southwestern Pennsylvania to rethink family engagement and solve problems collaboratively.[12] The LSX fellows, three of whom were leaders in districts with Parents as Allies programs, built upon a series of “empathy interviews” school leaders had conducted the year before, in which parents interviewed teachers and teachers interviewed parents in order, according to the Parents as Allies guidebook, to “better understand the different perspectives of these groups and their experiences with the school—positive, negative, and neutral.”[13] Those interviews helped prepare the LSX fellows to talk with parents, get their feedback, and enlist their expertise.

Designing New Strategies and Easy-to-Use Tools

The fellows were trained in design thinking techniques and had access to $7,500 ($2,500 for each of the three schools) to develop a new practice, tool, or resource that could help improve communication and build trust with families, especially those new to the school community. Each school varied widely in terms of demographics and income levels, and therefore needed different solutions. (Our blog post, “Designing Tools to Strengthen Communication and Relationships Between Families and Schools,” provides a fuller description of the schools and strategies, as well as links to PDFs of the flyers, maps, and websites created.) Below is a brief description of three of the four projects. Note: A fourth project, creating a redesigned school calendar for Avonworth Primary Center, also emerged from the parent interviews and will be described in an upcoming video produced by New America.

BRIDGE Builders at Avonworth

At Avonworth Primary Center, a K–2 school, Principal Scott Miller hosted a dinner and roundtable discussion with families that had moved to the school district after the school year had started. Miller’s school boundaries encompass many long-settled families in the middle-income range (15 percent of students qualify for free-and-reduced price lunch) but the population is also growing, with many new families moving to the area. He wanted to find out what problems come from arriving mid-year. Contrary to Miller’s initial assumptions, parents felt well connected with the school and their child’s homeroom teacher, but they said they wished they could connect with families of other children in their new neighborhood. To this end, Miller and the other fellows designed a program they call the BRIDGE Builders—Building Relationships, Inspiring Dialogue, Growing Education—connecting families who transition mid-year to family representatives from each of Avonworth’s five neighborhoods.

Community Resource Maps Around Duquesne

At Duquesne K–8 School, fellows created a neighborhood map in response to the wide range of needs raised by parents in anonymous questionnaires and one-on-one empathy interviews with the principal and LSX fellow Erica Slobodnik. At this school, in which 100 percent of students qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, and in which many newcomers speak a language other than English, families requested support finding a range of community resources including housing, child care, mental health services, transportation, internet access, and food pantries. So the fellows designed and produced a printed and online interactive map to address this need. They worked with the school resource team to identify local organizations, created the visuals for a paper version, and elicited feedback from parents by showing them the map during morning drop-off. They used that information to develop second and third drafts. Keeping in mind the community’s language needs, they translated the map into all three languages spoken by families in the school and used icons to ensure the map will be usable regardless of literacy level.

LSX fellows created a resource map for parents of Duquesne K-8 School, south of Pittsburgh. Through interviews with parents and help from the school’s social services liaison, the LSX fellows developed this map (in print and digitally).

Source: Photos by Elise Franchino used with permission

Mobile-Friendly School Website at Lockley

At Harry W. Lockley Early Learning Center, a K–2 school in New Castle with 100 percent of students qualifying for lunch assistance, Assistant Superintendent Tabitha Marino and her staff conducted empathy interviews and gathered survey data from families on their experiences with the school. They learned that while parents appreciated the abundance of options for communication, they felt that there were too many platforms. They also described the district’s website as challenging to navigate and noted that they accessed most information on their mobile phones. In response, Marino and her fellow fellows developed a streamlined website with staff using flexible and adaptable Padlet software and made it specific to the Lockley school, with contact information for teachers and staff, videos to help parents with new software, school calendars, and other resources families might seek. The team also designed a flyer with a QR code, which enables parents to use their mobile phones to quickly get to the website. The flyer will be inserted into the plastic transparent front sleeve of every red “take home” student folder.

Learning from the Process of Slowing Down and Seeking Feedback

The tools above will be rolled out to kick off the 2025–2026 school year. Principals and other leaders at these three schools will be able to track how much they are used by applying analytics technology (e.g., tallying the timing and frequency of QR code scans and website page views), and by collecting anecdotal and survey evidence from parents and teachers.

Yet if leaders focus only on the effectiveness of the tools, they will miss a key point that emerged over the year: The process of building the tools created a notable impact of its own. That process helped to change mindsets among LSX members of the team, especially among the school leaders who are often under extreme time pressure to roll things out quickly. This new approach required taking the time to hear ideas from parents and build opportunities for feedback loops. The work focused on “actually listening to our parents and seeing, ‘what do they want?’” Slobodnik said.

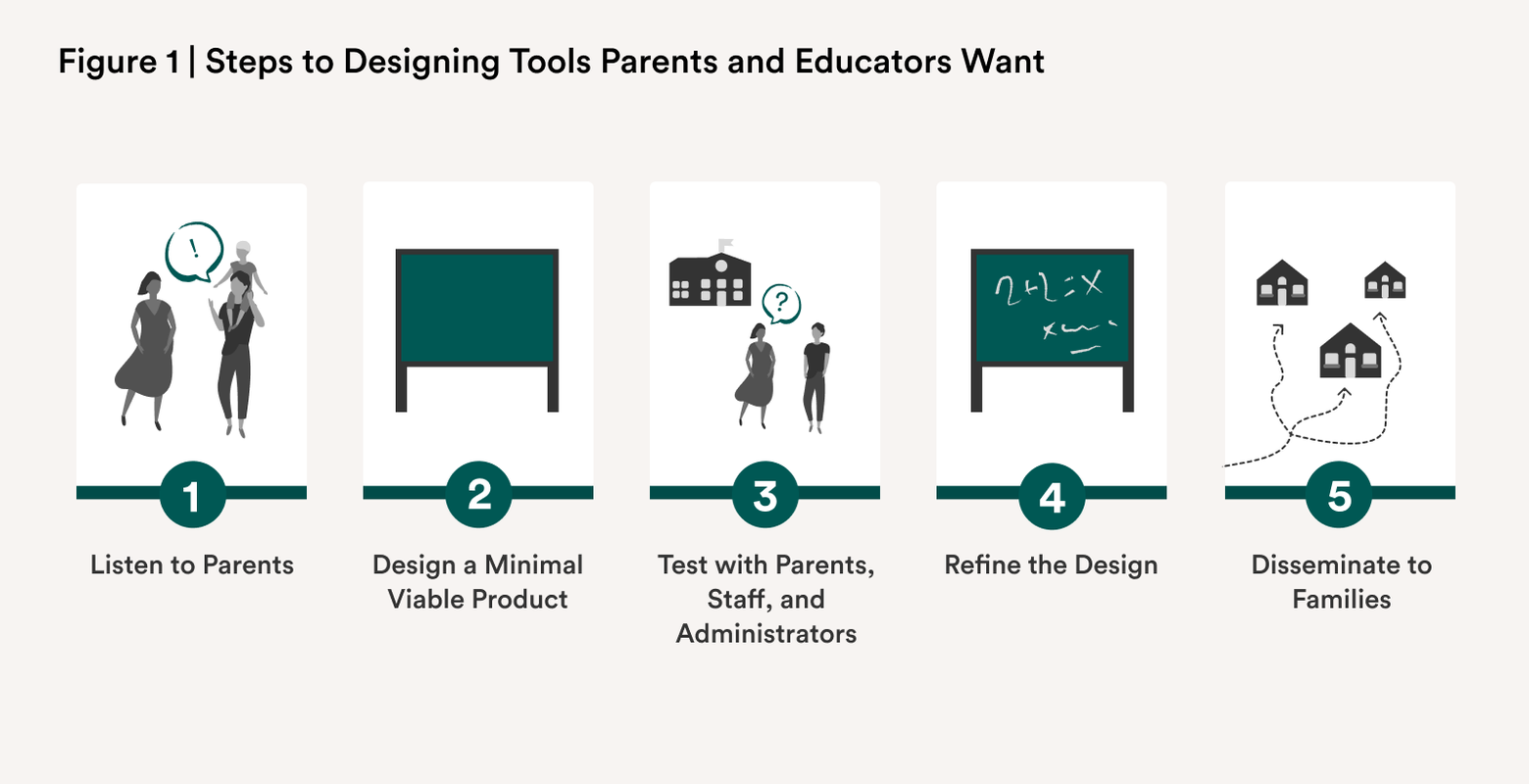

After listening, the school leaders were able to iterate on their designs with the help of outside experts in journalistic interviewing, user testing, and parent engagement. The design-thinking approach also illuminated the importance of producing an early prototype or “minimum viable solution” and asking users for feedback that would be used to help finalize the design (see Figure 1). “One powerful element of this process and of this experience,” Miller said, “is setting aside the direct time and the intentional time to collaborate and get feedback."

Perhaps most importantly, the process put human connection and family needs at the center of the problem-solving process, instead of focusing solely on information delivery. In schools, where there is a huge amount of new information for parents each year (school bus schedules, academic calendars, teachers’ rules and expectations, curricula, reading assignments, new apps and software programs, report-card systems, and so on), educators can feel pressed to get all the information out to families as fast as possible. The LSX and Parents as Allies models encouraged school leaders to slow down. They discussed empathy interviews with the other fellows, strategized about the most pressing problems and what solutions could have an impact, and moved into the design phase with parents as key partners.

These kinds of processes, especially as they lead to positive responses and more engagement from parents, have widespread potential. We hope they will inspire other education leaders to build in feedback mechanisms that enable schools to evolve with community needs as they tackle different problems.

Replicating Success in More Schools: Five Suggestions for Policymakers

In a project like this, outcomes data initially take the form of testimonials and evidence of changes in school-system processes, not student test scores. We recognize that seeing and measuring the impact of this change on children’s learning and families’ sense of partnership with schools requires a longer time window and more robust measurement tools. But given the decades of scientific research showing positive academic outcomes tied to better engagement with families, and given the momentum behind the parents’ rights movements today, policymakers should seize the opportunity to build out more of these kinds of initiatives and evaluate their impact.

Our experience in southwest Pennsylvania leads us to these five recommendations for education policymakers, whether on school boards or in state agencies and governor’s offices:

- Take an expansive approach. Instead of stipulating at the outset exactly what family engagement and its impact should look like, recognize that school leaders, teachers, parents, and caregivers will need time to build relationships and develop ideas together that match their local contexts. The map, website, and bridge-building program that emerged from this project were made possible by superintendents and other leaders who were willing to take chances on new approaches and who had open minds about what kinds of impact data and outcomes might emerge. The process was given as much respect as the product.

- Measure impact in nontraditional ways. Over the past four years, Parents as Allies has helped school leaders take note of not only common measures of success (such as the number of participants) but also the uncommon ones, such as taking enough time over conversations with teachers and family members to learn that it is, say, a child’s grandmother who is the more effective person to talk with about a child’s literacy growth. Qualitative data collection (interviews with families and teachers, for example) can enable schools to gather powerful information about impact. This approach also helps to encourage new ways of connecting with parents who are not often heard from or seen at school events.

- Provide time for co-design. Designing solutions with families and documenting, testing, and evaluating new tools and approaches takes time. At the Avonworth Primary Center, success emerged when the principal was able to pay for roundtable dinners designed to elicit parents’ ideas for solving tough problems. At Duquesne K–8 School and the New Castle Lockley Early Learning Center, leaders opened up time and space for parents to provide feedback on different communication tools, for interviewers to document their critiques, and for new versions to be developed and brought to parents for more feedback. This iterative process showed respect for parents’ ideas and improved the quality of the tools themselves.

- Enable honest conversations. Encourage a trusting environment where people can discuss what works and what doesn’t and admit where parents feel included and where they don’t. In this model, we brought in outside innovators whose goal was not to overturn and disrupt but instead to partner, share ideas, show respect, build on strengths, and gain new insights and learnings that they can apply in their own work.

- Encourage educators to use new family engagement models. Professional learning programs (continuing education as well as degree and certificate programs in higher education) should expose teachers and principals to the elements of design thinking, co-design, empathy interviewing, and cross-sector collaboration. All these ideas can better serve schools and families. Create incentives (such as funds for innovation and opportunities for professional recognition) for educators to get involved in these cross-sector initiatives and bring back ideas to their own schools.

Conclusion

Within just nine months, education leaders were able to connect more deeply with the families in their communities. They designed, built, tested, fixed, and tweaked new communication resources and trust-building programs for their parents and learned from each other. They shared ideas and experiences with experts in the worlds of research, journalism, children’s publishing, and tech-based social entrepreneurship. What’s more, the fellows in this project had the rare opportunity to visit schools, talk to parents, tackle real-world problems, and gain a deeper understanding of the challenges of keeping schools humming and families happy. This experience doesn’t have to be an anomaly. State and local leaders and policymakers can set the conditions for these types of initiatives by creating incentives for educators to get involved in cross-sector collaborations, allowing time to foster relationships and build trust, and setting up systems for listening to what parents want.

Notes

[1] Throughout this brief, we use the term parents as shorthand for parents, other family members, and caregivers who are raising children.

[2] LSX published a brief with the Brookings Institution in 2023 to describe its model and how it changes mindsets. See The LSX Model of Cross-Sector Collaboration: Tackling Wicked Problems and Catalyzing Creativity.

[3] For a few landmark research reports about family engagement since the early 1990s, see Anne Henderson and Nancy Berla’s report, A New Generation of Evidence: The Family is Critical to Student Achievement, written for the National Committee for Citizens in Education in 1994, which covers 66 studies, reviews, reports, analyses, and books. Eight years later, Henderson worked with Karen L. Mapp on A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement, which was published by Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL) in 2002. Other reports include Karen L. Mapp and Paul J. Kuttner’s 2013 report published by SEDL in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Education, Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity‑Building Framework for Family–School Partnerships, and the 2015 study by Maria Castro, Eva Expósito‑Casas, Esther López‑Martín, Luis Lizasoain, Enrique Navarro‑Asencio, and José Luis Gaviria, “Parental Involvement on Student Academic Achievement: A Meta‑Analysis,” which can be found in Educational Research Review.

[4] Studies that delve into the impact of these relationships include the following: Descriptions of parents and teachers’ viewpoints are part of the 2014 study, “Congruence in Parent–Teacher Relationships: The Role of Shared Perceptions,” by Kathleen M. Minke, Susan M. Sheridan, Elizabeth Moorman Kim, Ji Hyoon Ryoo, and Natalie Koziol in The Elementary School Journal. Scholars Alisa Hindin and Mary Mueller examine survey results from teachers engaged in family-school partnerships in their 2016 article, “Creating Home–School Partnerships: Examining Urban and Suburban Teachers’ Practices, Challenges, and Educational Needs,” in Teaching Education. Additional studies looking at factors important for family-school programs include William Jeynes’s 2010 article, “The Salience of the Subtle Aspects of Parental Involvement and Encouraging that Involvement: Implications for School-Based Programs” in Teachers College Record; Karen Lasater’s 2016 article, “Parent–Teacher Conflict Related to Student Abilities: The Impact on Students and the Family–School Partnership,” in School Community Journal; Joyce L. Epstein’s 1995 article, “School/Family/Community Partnerships: Caring for the Children We Share,” in Phi Delta Kappan; and the 2002 book by Joyce L. Epstein, Marvis G Sanders, Beth S. Simon, Karen Clark Salinas, Natalie Rodriguez Jansorn, and Francis L. Van Voorhis, School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action, published by Corwin Press.

[5] This distinction gained widespread appeal after Larry Ferlazzo, a California educator and author of many popular books on teaching, described it in his 2011 article, “Involvement or Engagement?” in ASCD’s EL Magazine.

[6] This quote is from the “commitment” section of the infographic explaining NAFSCE’s strategic framework.

[7] For more on the link between the ways parents talk to children and children’s literacy skills, see the 2013 article in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “Quality of Early Parent Input Predicts Child Vocabulary 3 Years Later,” by Erica A. Cartmill, Benjamin F. Armstrong, III, Lila R. Geltman, and John C. Trueswell.

[8] Several studies show this connection. See the 2011 article, “Family Involvement and Educator Outreach in Head Start: Nature, Extent, and Contributions to Early Literacy Skills” in Elementary School Journal; the 2016 article, “Proactive Parent Engagement in Public Schools: Using a Brief Strengths and Needs Assessment in a Multiple-Gating Risk Management Strategy,” in the Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions; and the 2013 article, “Defining Family Engagement Among Latino Head Start Parents: A Mixed-Methods Measurement Development Study” in Early Childhood Research Quarterly.

[9] For more, see two pieces in Journal of Latinos and Education: Mari Riojas-Cortez and Belinda Bustos Flores’s 2009 article, “Sin Olvidar a los Padres: Parents Collaborating Within University and School Partnerships,” and Tami De La Garza and Lisette Moreno Kuri’s 2014 article, “Building Strong Community Partnerships: Equal Voice and Mutual Benefits.”

[10] In 2020, Education Development Center & SRI International published Strategies for Success in Community Partnerships: Case Studies of Community Collaboratives for Early Learning and Media. It is a case study with details on 31 partnerships among public media stations and organizations such as schools, libraries, afterschool program providers, parent and family advocacy groups, and housing authorities. The initiatives were developed and implemented between 2015 and 2020 as part of the CPB-PBS Ready To Learn Initiative funded by the U.S. Department of Education.

[11] A co-author of this brief, Susan Beltrán-Grimm, has extensive experience co-designing learning materials with Spanish-speaking parents. See her 2023 article, “No Solamente Ellos Aprenden, Aprendemos Nosotros También (Not Only Do They Learn, We Learn Too): Latina Mothers' Experiences with Co-Design Approaches in Creating a Math Activity for Their Children,” in the Journal of Latinos and Education.

[12] Another key element of the Parents as Allies program is to apply “conversation starter” tools developed by Emily Markovich Morris of Brookings Institution to spark and deepen dialogue on the purpose of education. For more on how the Parents as Allies program got started, see Emily Morris and Yu-Ling Cheng’s 2025 article in Education Sciences, “Parents as Allies: Innovative Strategies for (Re)imagining Family, School, and Community Partnerships.” The conversation starter tools are available for download through the Brookings Institution.

[13] This quote is from page 9 of A Guidebook for Bridging the Ocean Between Home and School Through Innovative Family-School Engagement, published by Kidsburgh in 2021. The guidebook is full of examples of practical and inspiring activities and programs started and tested by more than 30 schools.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the many colleagues and fellows who provided insights and feedback throughout the conception and writing of this brief, including Yu-Ling Cheng, Carrie Gillispie, Tabitha Marino, Tara Garcia Mathewson, Scott Miller, Cara Sklar, and Erica Slobodnik. Thanks also to Kristine Malden of Slab Design and our LSX co-founders Roberta Golinkoff and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek for strategic guidance throughout the project and to our editorial partners at New America, Katherine Portnoy, Amanda Dean, Natalya Brill, and Sabrina Detlef. We thank the Jacobs Foundation for its partnership in building the Learning Sciences Exchange and supporting it for seven years. And we are very grateful to The Grable Foundation, whose support enabled us to partner with Parents as Allies; select and support our fourth cohort of fellows; produce reports, videos, and tools; and continue to strengthen our LSX network, which is using cross-sector approaches to respond to policies affecting children and tackle tough education problems.